How Do You Reside: The Legendary Japanese Novel that Virtually By no means Was

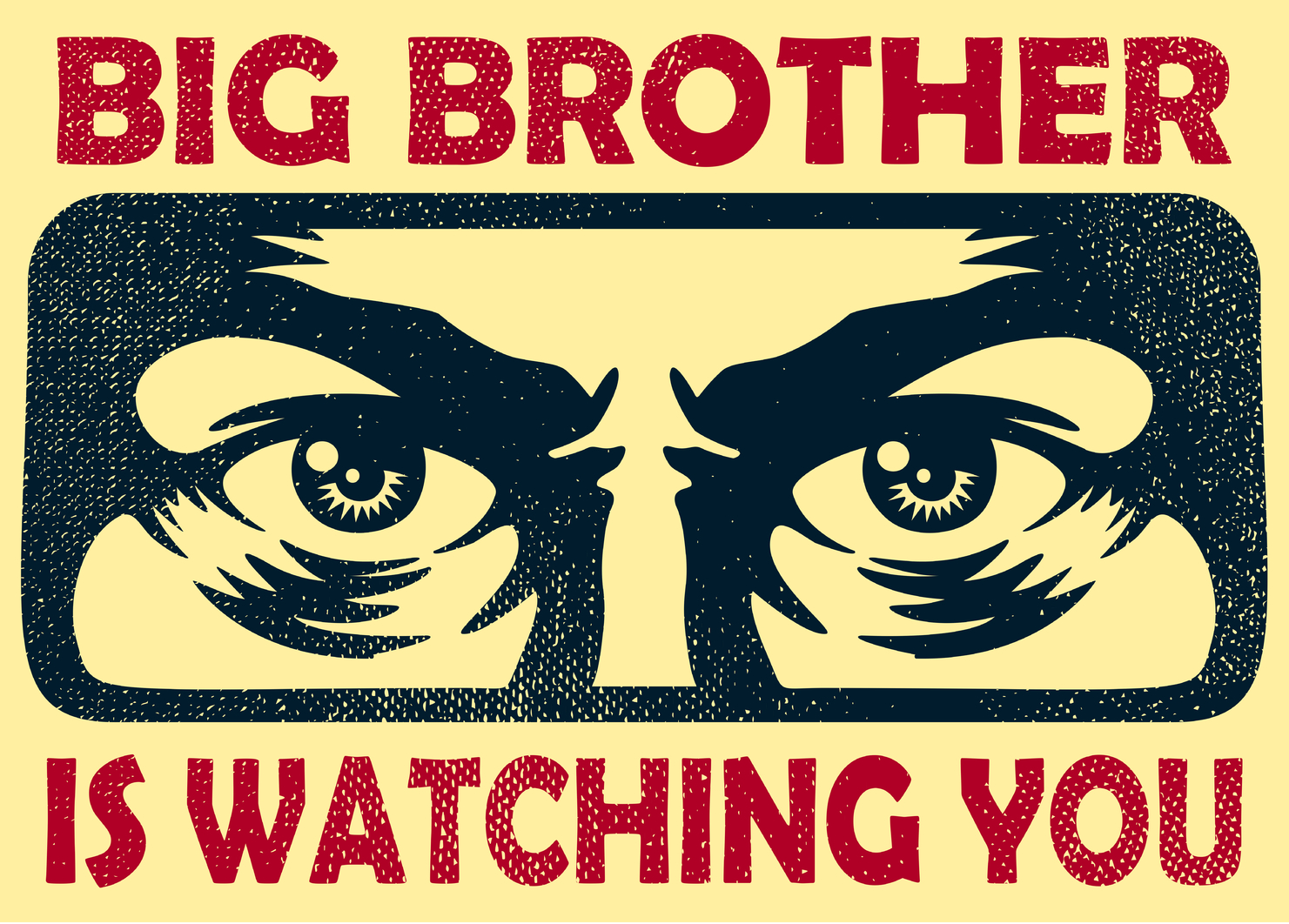

When Genzaburo Yoshino penned How Do You Reside? in 1937, a piece of anti-authoritarian genius that continues to be on the classical arts curriculum as we speak, it was an train in sociopolitical legerdemain. For functions of stealth, Yoshino packaged an ethics e book of then-outlawed Western concepts as a coming-of-age youngsters’s novel to keep away from the prying eyes of the TokyoImperial Japan’s “Thought Police.”

If one had been to learn solely the chapters narrated by an omniscient voice that follows the protagonist, a 15-year-old boy in interwar Tokyo nicknamed Copper, the sleight of hand would not be so obvious. These chapters are sometimes as not healthful, as Copper passes the seasons by visiting a good friend who’s making tofu for the household store, devising his personal commentary for a university baseball recreation, or reuniting together with his schoolmates after a quick falling out.

Nevertheless, paired with intermittent essays written to Copper by his uncle, which contact on Newtonian physics, the greatness of Napoleon’s rags to riches arc, what it means to be human within the 20th century and dwelling one’s life in pursuit of liberty and self-actualization, it turns into a completely completely different proposition.

Most Japanese as we speak will a minimum of know the title, whether or not or not they’ve learn it, however How Do You Reside?‘s journey to literary immortality wasn’t with out its travails.

The Thought Police

By the Thirties, Japan was presided over by the identical fascist dictatorship that will lead it into conflict in 1941, and the Tokko had been tasked with implementing the Public Safety Preservation Regulationenacted to ban concepts deemed anti-capitalist or contravening the “nationwide essence.”

Yoshino, a philosophy and literature graduate working on the College of Tokyo library, fell afoul of the legislation a number of years earlier than How Do You Reside? was printed when he was imprisoned for 18 months in 1931 for attending conferences with identified socialists. This solely served to strengthen his idealism.

Upon launch, his good friend, the novelist and playwright Yuzo Yamamoto, supplied Yoshino the chance to put in writing the final e book in a sequence for youthful readers. Initially deliberate as an ethics textbook, Yamamoto prompt to Yoshino that the novel would work as a extra subversive and clandestine medium for delivering the e book’s classes. Thus, How Do You Reside? took the type of parables and essays, ostensibly at youngsters, which allowed it to thrive undetected, turning into a high 10 bestseller in its 12 months of launch.

Yoshino and Yamamoto efficiently pulled the wool over the federal government’s eyes, however just for a handful of years. By 1942, the Tokyo had caught wind of the novel and took it out of circulation, solely to rerelease it in 1945, excised of its capitalist critiques and not-fit-for-public-consumption beliefs.

How Do You Reside? would stay life anew, nonetheless, republished in its unique kind earlier than Shoichi Haga created a 2018 manga adaptation that offered two million copies — greater than some other e book printed that 12 months.

The following step within the novel’s journey will likely be guided by legendary Studio Ghibli pioneer Hayao Miyazaki, who’s reportedly popping out of retirement to make one ultimate animated movie based mostly on Yoshino’s work. Miyazaki’s adaptation, anticipated to observe the story of a younger boy who reads How Do You Reside?is being left as a present to the auteur’s grandson as he prepares to “transfer on to the following world,” says the movie’s producer Toshio Suzuki.

Life Lesson in How Do You Reside?

How Do You Reside? was translated into English by Bruno Navasky final 12 months and its unorthodox format, which Neil Gaiman compares to Moby Dick within the e book’s foreword, and enduring life classes present a lot worth for contemporary readers.

Copper’s uncle is his idol and pseudo-father determine, so it is becoming that every chapter within the boy’s life segues into his uncle’s pocket book. Right here, he scribbles thematic letters to his nephew, masking concepts akin to humanism, progress, individualism and points of sophistication and social conformity, that evoke the enlightenment thinkers of Europe.

“Nonetheless,” his uncle writes after he and Copper have been gazing out at Ginza from a division retailer rooftop, “to see your self as a single molecule throughout the huge world — that’s in no way a small discovery.”

Later he writes to Copper, in a letter titled “On True Expertise.”

“If it means something in any respect to stay on this world, it is that you have to stay your life like a real human being and really feel simply what you’re feeling. This isn’t one thing that anybody can educate you from the sidelines, irrespective of how nice an individual they could be.”

Or as he notes on greatness:

“However greater than humbling ourselves to those folks, we should be daring sufficient to ask questions. Akin to ‘What did they accomplish utilizing these extraordinary talents?’… And with extraordinary talents, is not it potential that one may simply as simply accomplish terribly dangerous issues?”

Within the context of Thirties Japan, the subtext of insubordination to the state is worn closely on Copper’s uncle’s phrases. Furthermore, it’s not possible to miss the maturity of those themes. Which raises the true query of the e book: Who’s it actually for?

Navasky sees a timelessness in Yoshino’s teachings and an software that goes far past the youngsters, and even adults, of interwar Japan. As he notes in an afterword, “It is a distinctive e book, and significantly worthwhile to us now, when violence in opposition to residents is on the rise, and impartial thinkers are being attacked by their governments each right here and overseas.”

On the face it, fusing a e book about childhood friendships, like Stephen King’s The Physique, with a piece akin to Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Man, makes for a clumsy coupling. However this is likely one of the nice strengths of the novel: its malleability. And Yoshino bent the shape to his will making a murals that is each decidedly of its period, but eternal in its ethical implications.

How Do You Reside? might have teetered on the point of dying in Nineteen Forties Japan, however we must always all be grateful that it has cemented its place within the canon of Japanese literature.